My name is Iryna Smaznova. I am the Head of the Department of philosophy, Professor, Doctor of Sciences in Law, National University «Odessa Law Academy» (Odessa, Ukraine); Robert G. James Fellowship Winner, the Harvard Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study (Cambridge, USA). I was a visiting researcher at the University of Jerusalem (Israel). I am currently a visiting researcher at the University of York (UK).

Before the war, my life in Ukraine was well-defined, simple, and clear—as a lecturer, teacher, researcher, woman, and mother to a young son.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine changed everything, dividing life into "before" and "after." I spent a year and a half under daily and nightly attacks in my hometown, Odesa—an extraordinary, atmospheric Ukrainian city by the sea, shaped by international influences, tolerance, cultural diversity, and a blend of languages. Yet, the war transformed this once lively, million-strong city into something unrecognisable—dangerous, cold, and abandoned. Frightened, abandoned pets roamed the streets, which were almost empty of people and cars. The city endured relentless shelling and bombardment, causing destruction and loss of life. But we knew that conditions in occupied territories were even worse. The psychological strain of a looming attack from the sea or from Mykolaiv was constant.

I became accustomed to living with persistent fear, sleepless nights, and sheltering in a basement with my young son. Whenever bombs fell, I covered his ears to soften the noise and held him close, shielding him with my own body. The idea of evacuation never crossed my mind, even for my child—I had resolved to stay and resist. My sister and I genuinely discussed how we would prepare Molotov cocktails and throw them at tanks. We found strength in the heroic resistance of Azov fighters in Mariupol. Our fear of occupation was well-founded. When Bucha, Irpin, Borodyanka, parts of Kyiv, Chernihiv, Kherson, Kharkiv, and many other cities were liberated, the world finally saw the horrors we had long feared.

And yet, life continued. Those who remained in Odesa carried on working. My university resumed online teaching just two weeks after the war began—our experience during the Covid pandemic had prepared us well for remote learning.

Teaching helped me maintain discipline, gave me a sense of purpose, and allowed me to cling to some form of normality. But soon, things became even harder, as infrastructure was destroyed. Often, lecturers and students were unable to access online classes. Sometimes, we went an entire week without electricity. At times, power was available for only a few hours a day. Despite the blackouts and freezing temperatures, I resumed my research. I wrote my thoughts and ideas by candlelight, determined to keep working. I wrote with anger and fury, which fuelled my productivity. Later, I searched for places—cafés with generators or friends whose homes had electricity according to the scheduled outages—where I could transfer my notes to an electronic format and submit them. Months of working in darkness and cold eventually took a toll on my eyesight.

One night, a missile or drone exploded near my home, and I finally considered to leave Odesa, at least for a while. By then, the city had already seen deaths and injuries—not to mention the destruction of residential buildings. But that particular explosion was the final straw.

It was the middle of the night. The siren wailed, but I was so exhausted that I ignored it—I chose not to wake my son and not to descend into the basement again. I refused to spend another night underground. It was my silent protest against the war. But the explosion was so powerful that its glow was visible from my window. I had heard many explosions before, seen their aftermath, known of victims, and listened to horrifying accounts from those who had escaped hell in Eastern Ukraine. But I had never seen an explosion so close—just a few dozen metres away. Panic surged through me, and I grabbed my son from his bed so abruptly that I severely injured my back. I felt distressed, heartbroken, yet resolute. That was the moment I decided to apply for academic grants.

I submitted several of my research projects to universities worldwide, and some were successful.

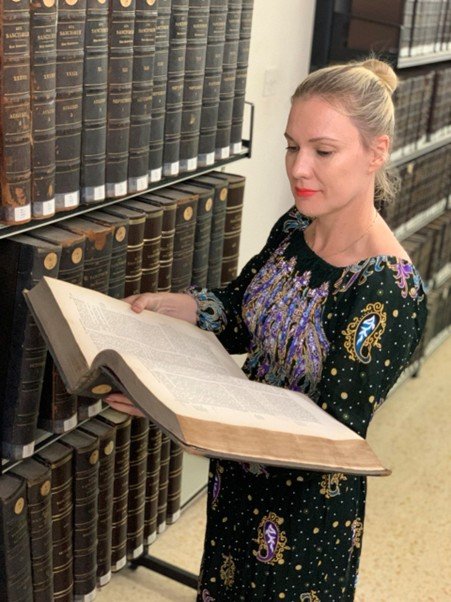

I am deeply grateful to The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel), which awarded me my first grant and gave me the opportunity to start anew.

I spent three months there, meeting extraordinary professors and researchers.

Returning to Odesa, I resumed teaching in wartime conditions, now offline. Without electricity, lessons were moved to classrooms, as online learning was no longer possible. Air raid sirens interrupted our lectures, and I took my students to shelter in the basement.

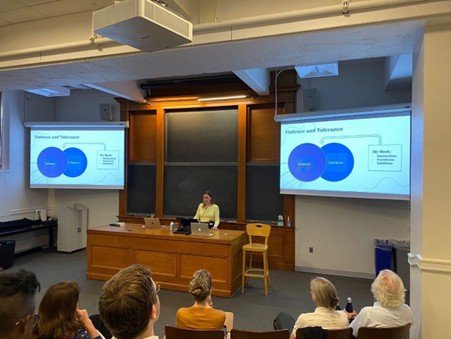

That winter, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem nominated me for an award at Harvard University. My deepest gratitude goes to my mentors Katya Assaf (Jerusalem) and Lisa Herzog (Netherlands), who profoundly shaped my academic journey. From September 2023, I became a fellow at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute, joining 50 scholars from around the world in a prestigious programme. Those months were transformative—filled with learning, career development, and connections with scholars from diverse disciplines. I forged invaluable friendships with many of them.

Later, I returned to Odesa for a month and a half before securing a new research grant at the University of York (UK). Here, in the Department of Political Philosophy and International Relations, I continue my academic work. I am profoundly grateful to my mentor Alfred Moore, my colleagues Ruth Kelly and Tony Heron, as well as The British Academy and the UK government, for creating programmes that support scholars at risk.

In conclusion, I would like to share my personal motto, which has guided me both in life and in my academic journey—Eyes are afraid, but hands keep working.